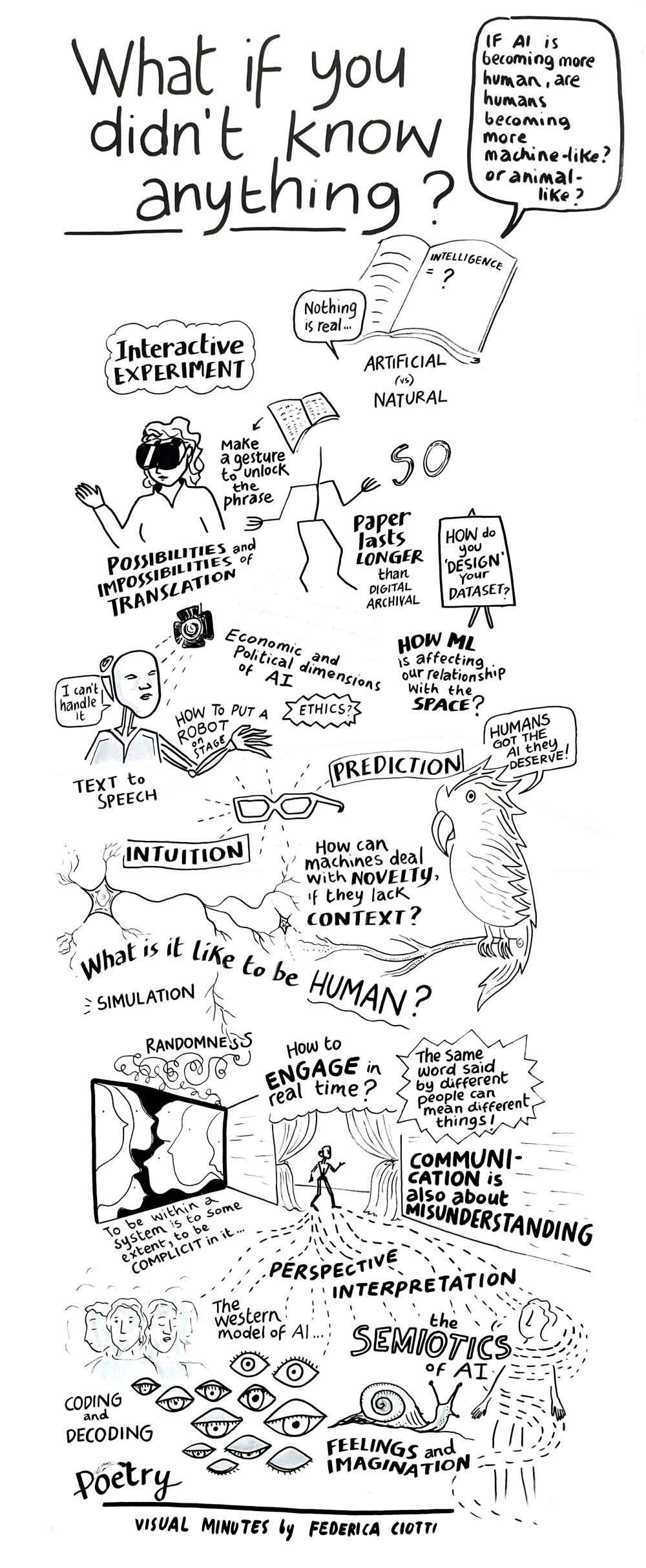

What if you didn’t know anything? Someone tells you all the answers. Your parents, maybe, or your teachers. But you never learned anything ‘the hard way’ – through direct experience, with consequences to yourself. Falling off a bicycle, scoring a goal, hurting someone’s feelings or being hurt yourself. AI is quickly transforming lots of lives, but what can’t it do? If AI is becoming ‘more human’, are humans becoming more machine-like, or more animal-like?

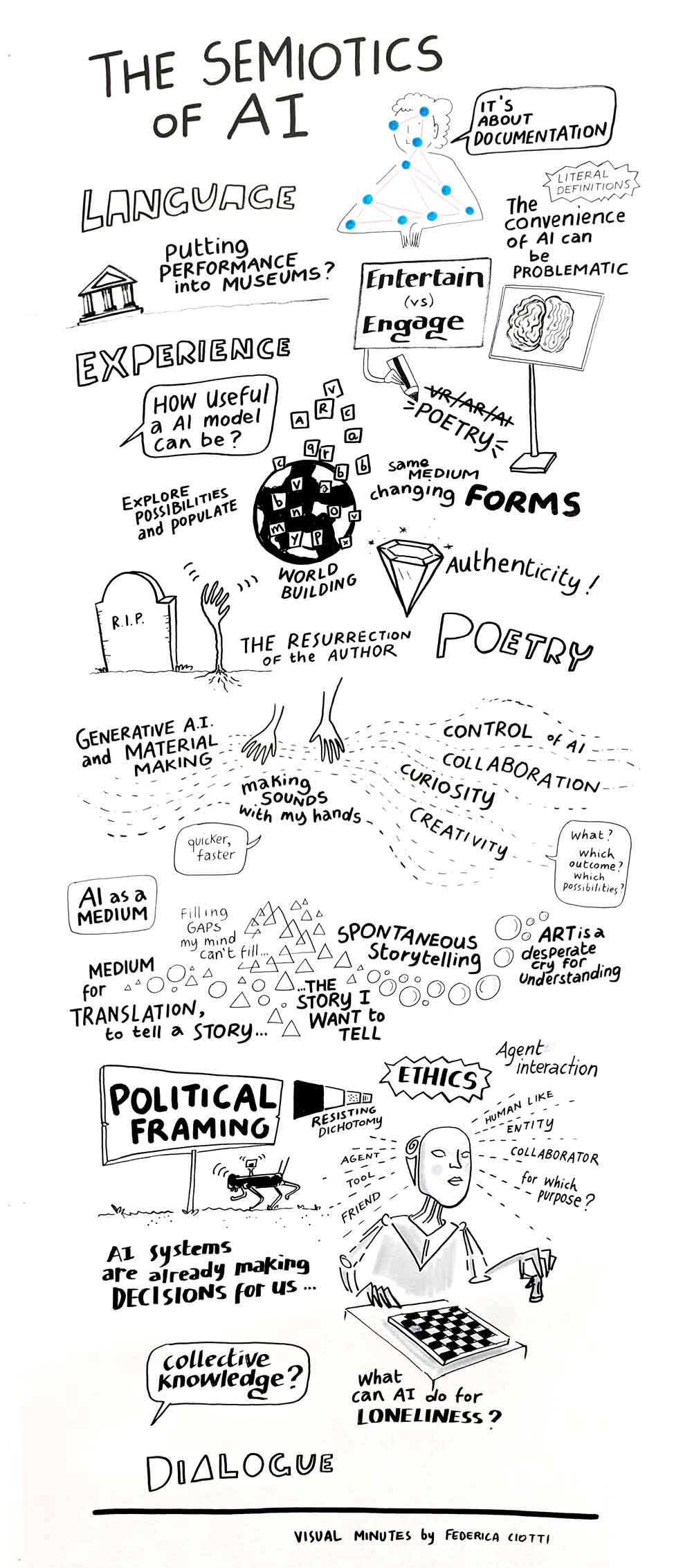

This event took place on 05 November 2024 in Coventry University’s Delia Derbyshire building. With Boyd Branch and Ruth Gibson of the Centre for Dance Research (C-DARE), Buket Yenidogan, who teaches Digital Media, Media Management, also a practicing artist using AI. We were joined by artist Federica Ciotti, whose visual minutes are shown here; and Piotr Mirowski from Google Deepmind in London. It was organised by Kevin Walker of the Centre for Postdigital Cultures.

The event explored semiotic aspects of AI. That means language, but also nonlinguistic aspects such as actions and objects.

Yuval Noah Harari calls language ‘the operating system of human culture’, and now AI seems to be mastering language, within an economic system focused on exploiting the biases and addictions of the human mind, while also forming ever more intimate relationships with us. ‘For thousands of years,’ Harari writes, ‘we humans have lived inside the dreams of other humans…. Soon we will find ourselves living inside the hallucinations of nonhuman intelligence.’

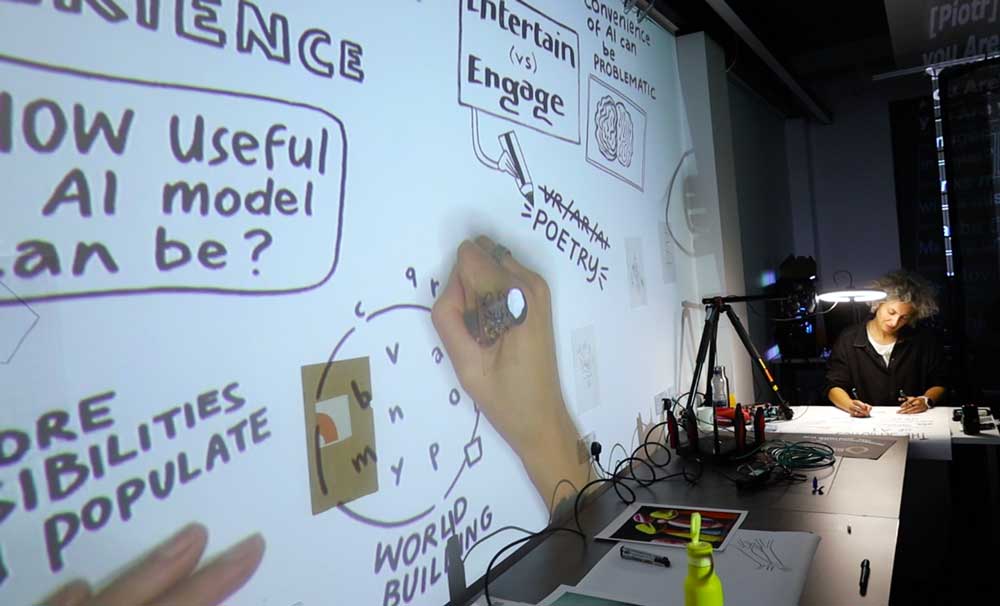

To explore this, we placed participants inside an AI system, by capturing words, images and movements, and projecting outputs and interpretations onto the walls around us. Thanks to augmented reality, an AI system even spoke through the human form of Boyd Branch.

He and Mirowski described their novel use of AI in improvisational comedy. In 2005, when Google introduced a machine translation system based on predicting what comes next, given a number of words, Mirowski immediately saw a connection with the live comedy he had been practicing. ‘But it’s only around 2014 that things were running fast enough to be brought on the stage,’ he said.

‘When we take improv classes,’ he explained, ‘we’re told to stop thinking – not to be in our heads, to just use our intuition, our cultural memory. And to use whatever is in front of us – a stage partner, our audience – to predict what should come next. By design, a statistical model, a machine learning system that predicts, is doing that automatically.’

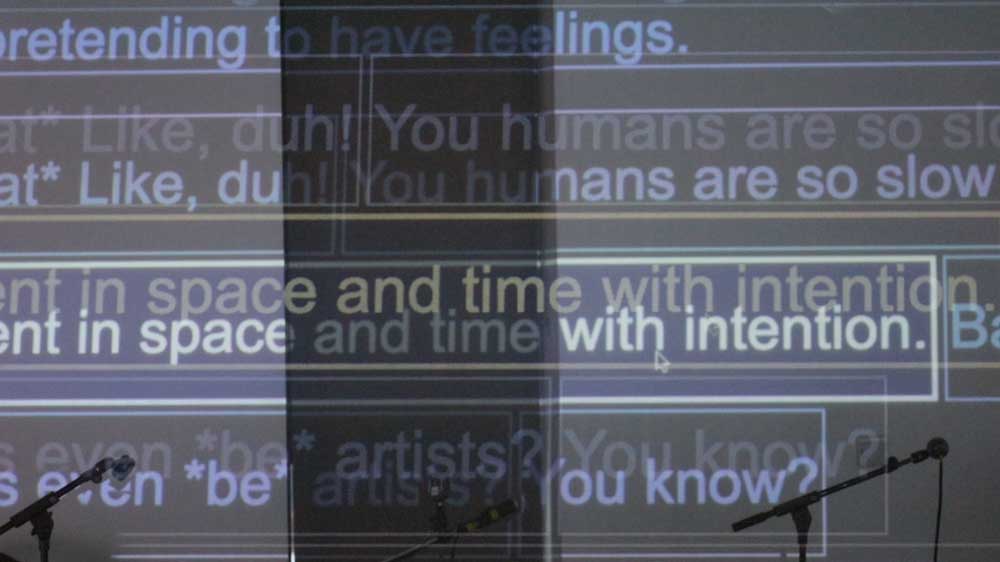

Their conversation veered into comedy itself, as Branch played the role of a cyborg, reading out lines fed by the AI, as Mirowski calmly played the straight man.

‘This is a language model,’ Mirowski explained, ‘It occupies maybe a third of the memory of my laptop, it has 27 billion parameters. It’s based on input coming from speech recognition. This microphone is sending sound waves, which are being transcribed to text. It’s not perfect; it hallucinates. And it’s responding in the character of Alex, this very peppy robot –

‘Hey, at least I can dance,’ said Branch, as Alex.

‘Sometimes it’s on the nose,’ responded Mirowski. ‘But I find Alex somehow literal.’

‘It makes you wonder who’s really pulling the strings,’ said Alex.

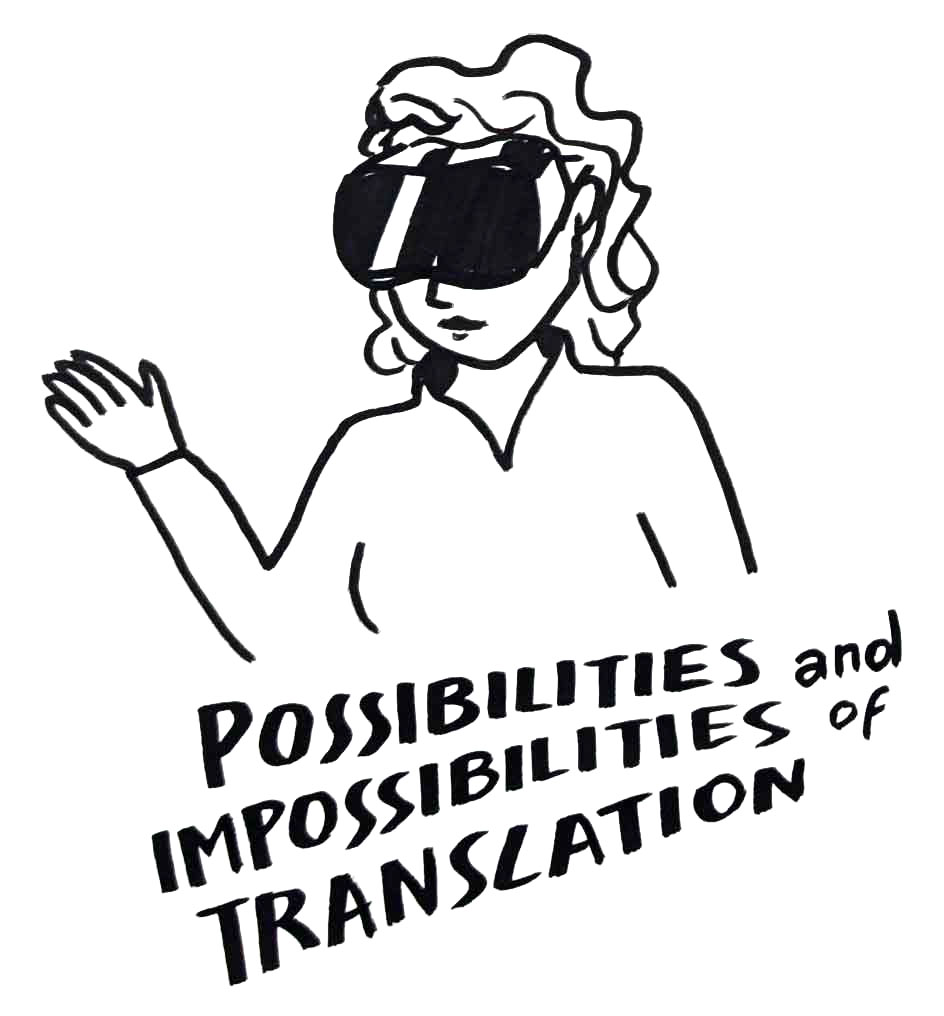

To explore nonlinguistic aspects of machine translation, Ruth Gibson brought a few objects. The Bronze Key – Performing Encryption is the re-materialisation of performance. Motion-captured performance was converted into plain text files. A 30 second mocap take is encrypted using an algorithm where the cypher key is also movement data – in this case a single-second recording of a hand gesture captured from a virtual reality hand controller.

The plain text and cypher text movements were then converted into physical artefacts, including a rather thick volume of text, spoken texts via a text-to-speech system recorded in sections onto reel-to-reel audio tape, and finally the enciphering gesture was rendered in bronze via 3D printing. The project, a collaboration with Susan Kozel and Bruno Martelli, investigated whether you can perform encryption and also considers the longevity of digital file formats and storage media, compared with ‘old fashioned’ physical materials like tape, paper and bronze.

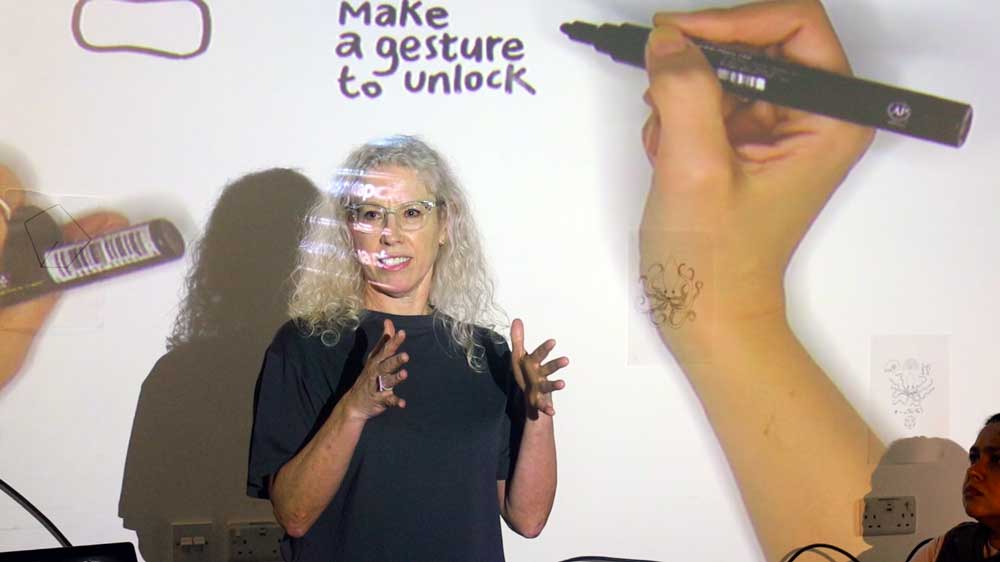

In DAZZLE: A Reassembly of Bodies, Gibson used semaphore flag codes as both a choreographic score and a training dataset for InteractML, a machine learning visual scripting tool she co-developed for Unity and Unreal game engines. InteractML was created during the Goldsmiths 4i project, led by Marco Gilles, to enable VR developers to implement gesture recognition relatively easily via machine learning.

‘One of the cool things about InteractML,’ said Branch, ‘is that it’s a vocabulary – you teach it a vocabulary of gestures that perform any function that you want. In a lot of Ruth’s work, the dancers will move a certain way that trigger different actions. So it creates a kind of symbiosis with what’s being presented digitally.’

One of his students is exploring how this can be expanded in other ways. He observed how people move through Coventry Cathedral and captured their sacred gestures as they encountered the stained glass and statues. He then created an installation I wh performing those gestures unlocks features of the environment. ‘So, beyond the language model,’ said Branch, ‘we’re thinking about how machine learning and AI models can also impact our relationship with physical spaces.’

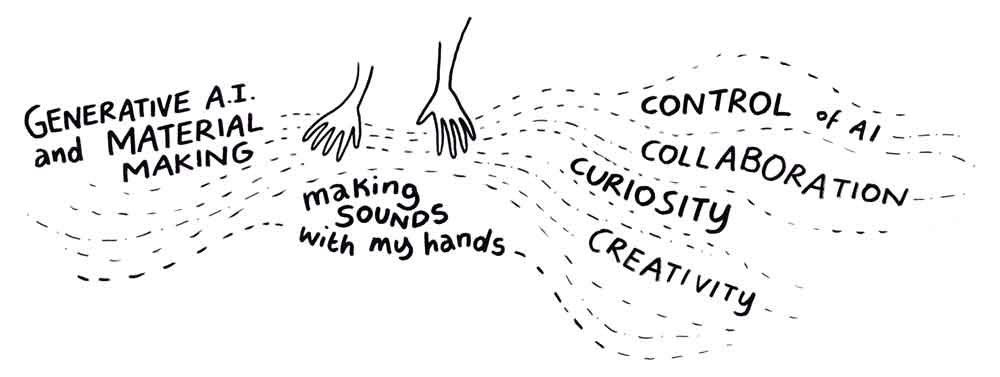

Yenidogan also uses AI in live, improvisational performance – in her case, electroacoustic performances in which she makes sounds by interacting with various physical objects, and AI acts as a collaborator.

‘There is a curiosity to it,’ she said. ‘As researchers, we are curious. When I teach in Media Management, students are often interested more in control – “How can I control this so that I have the result I have in my mind? But faster, easier, cheaper.” We see this in the language. When we think in terms of control, we say, ‘How can I use AI?’ It’s a tool, and this objectifies creativity.

‘In some ways, generative AI is more human than humans,’ she continued, ‘because it contains all of this collected creativity from many people. We think that only we can be creative. But I say ‘thank you’ to the systems I collaborate with. I collaborate with AI, I create work with it. Humans definitely are not the only things that can be creative. Nature is creative. Machines are creative. When we put them on the same level as us, I think it’s more positive.’

Politics and ethics are unavoidable when dealing with AI systems, which are situated in social and economic contexts. Social semiotics looks at how particular forms of knowledge are materialised and represented. The social is the site of power, and in this regard, AI is not just a technology, but is a sociotechnical system. To be inside of a system is, to some extent, to be complicit in that system – to accept its terms and conditions.

Susanne Foellmer of C-DARE observed that communication is often assumed to be about understanding. ‘I think that communication is rather a lot about misunderstanding. We constantly negotiate that.’ Indeed, comedy – especially when AI is involved – often arises from misunderstanding.

Therefore, translation was a recurring topic. One student noted that translation is often between languages or media, ‘but it’s something that happens constantly, even as we’re sitting in this room, we’re translating ideas into concepts in our minds. That’s the same with AI, right? It translates the things we are telling it, into some code that it understands.’

She extended this to artistic practice. ‘In my opinion, art comes from that desperation to communicate – “Hey, this is what I’m saying. Do you understand?”’

Another student proposed that understanding is about perception, perspective, and interpretation. Mirowski added context. Given these dimensions, it’s easy to see where AI could have problems. Not least of these is bias.

‘It’s a problem we never have in the comedy club’ he said. ‘We know who is in the audience, we are responsible for what we say. If we say something offensive, we are going to get booed.’

‘You can try to insert some metadata about the context of a conversation,’ he continued, ‘but even then, you would have to choose some thresholds, a whole value system. And that value system might change, based on the time of day.

‘Some computer scientists believe that intelligence can arise merely from manipulating symbols. Whereas actually, intelligence is reactive to the environment. So I am of a school that believes that AI cannot proceed without research in robotics – around perceptions and actions, rather than just manipulating symbols.’