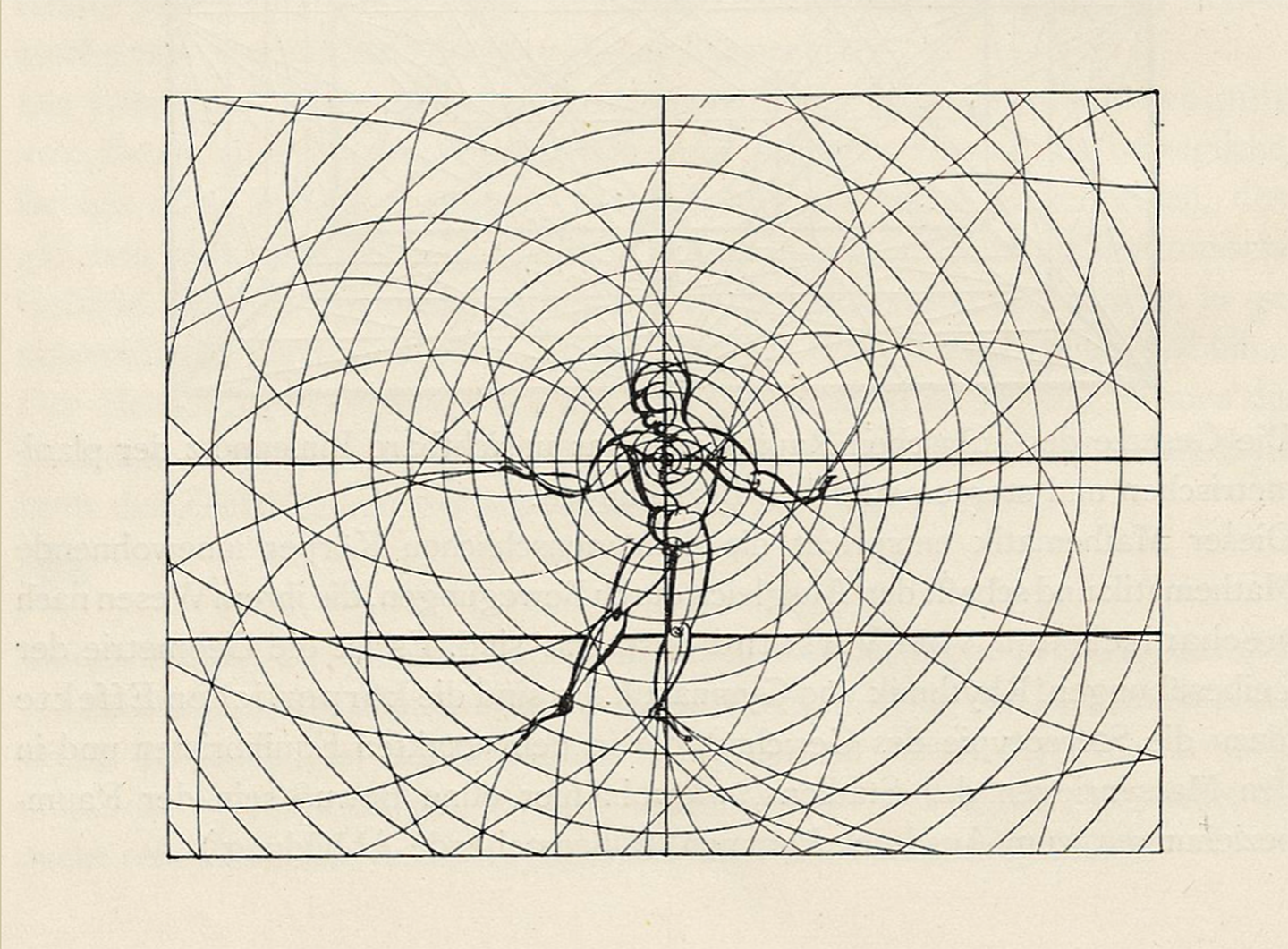

Image: Oskar Schlemmer from Notebook n.4 of the Bauhausbucher, 1925, from ‘The Automation of General Intelligence‘ by Matteo Pasquinelli

In this article, Matteo Pasquinelli writes that AI ‘actually emerged from the automation of the psychometrics of labor and social behaviors rather than from the quest to solve the “enigma” of intelligence’. His big-picture analysis challenges the Marxist assumption that means of production drive social relations, arguing for the opposite. He describes how labor already became “mechanical” on its own, before machinery replaces it – quoting Hegel, he writes, ‘labor that gives “form” to machinery’.

Mathematics, for example, became a primary means through which we coordinate with technology. ‘Mathematics is a human activity after all,’ he writes. ‘Like any other human activity, it carries the possibilities of both emancipation and oppression.’ Ancient rituals, counting tools, and “social algorithms” all contributed to the making of mathematical ideas, he says.

Pasquinelli’s discussion of automation, rules, and labour reminded me of Engeström‘s use of tools, rules and the division of labour in his activity theory diagram, for analysing what people do, how tools mediate what they do, and how contradictions in this mediated relation can drive innovation and change.

Complexity and control

During industrial times, the division of labor was relatively simple industrial ‘and its seemingly rectilinear assembly lines could easily be compared to a simple algorithm, a rule-based procedure with an “if/then” structure,’ he writes.

With computation came systems theories and cybernetics, which ‘started to investigate self-organization in living beings and machines to simulate order into high-complexity systems that could not be easily organized according to hierarchical and centralized methods.’

AI became a tool not just for automating labor, but also for imposing standards of ‘mechanical intelligence’, with all the racist origins of psychometrics and measures of comparative human intelligence. Following Pasqinelli’s assertion that increasingly mechanised social relations made way for increasing automation, he argues, ‘The design of a machine as well as the model of a statistical algorithm can be said to follow a similar logic: both are based on the imitation of an external configuration of space, time, relations, and operations.’

A single machine-learning model can automate lots of different tasks: assembly line work, driverless cars, language translation, image description. There is no technical distinction – they can all be represented by statistical modelling. This means that not only manual work but ‘knowledge work’ can be automated – including management. AI easily becomes the boss, and this is already the case with ‘gig workers’ like Uber drivers, Mechanical Turkers, anyone who works in logistics.

What to do?

In Pasquinelli’s approach grounded on mechanised labour, ‘Technologies,’ he writes, ‘can be judged, contested, reappropriated, and reinvented only by moving into the matrix of the social relations that originally constituted them.’ So any alternatives need to be situated in these social relations. A ‘collective “counter-intelligence,” has to be learned,’ he writes.